JAKARTA (Reuters) – An ambitious scheme to replant about a fifth of the land under palm oil in Indonesia is running far behind schedule, marking a blow to efforts by the world’s top producer to lift yields and fend off attacks on the sustainability of the crop.

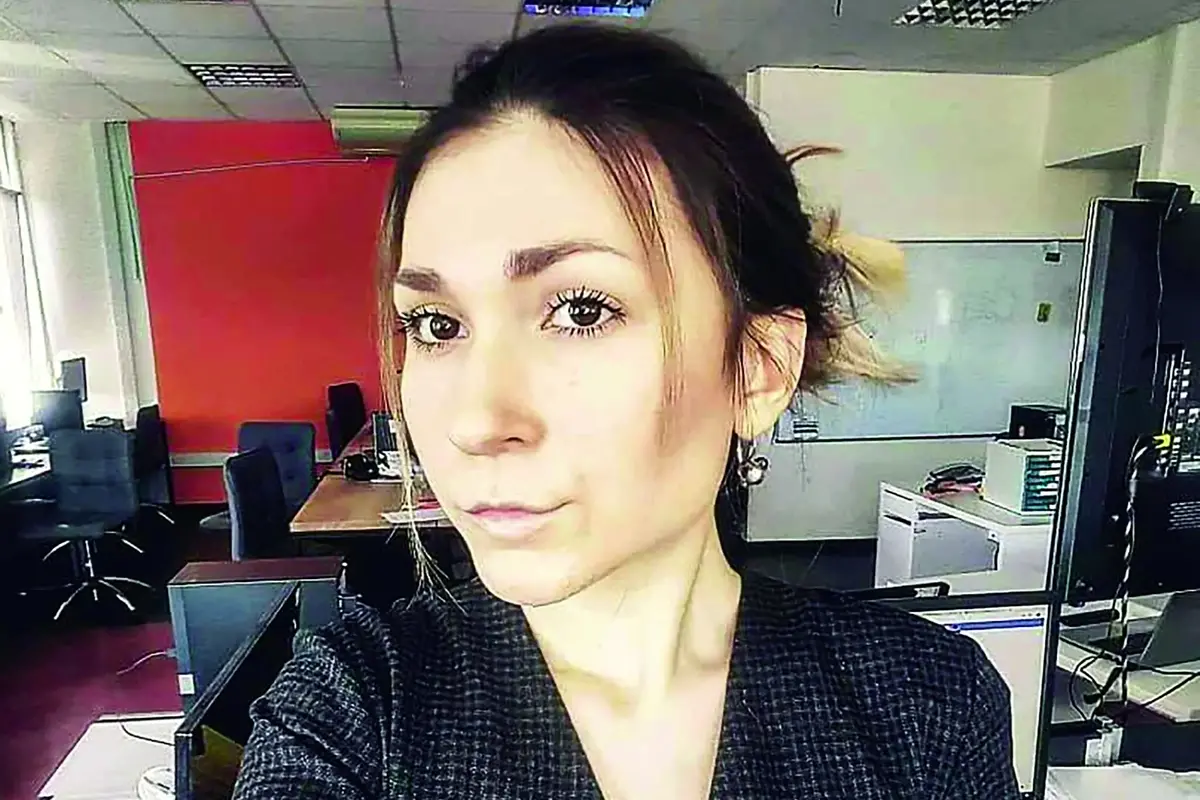

A worker shows palm oil fruits at palm oil plantation in Topoyo village in Mamuju, Indonesia, Sulawesi Island, March 25, 2017 in this photo taken by Antara Foto. Picture taken March 25, 2017. Antara Foto/Akbar Tado/via REUTERS

The target of replanting 2.4 million hectares of palm grown by smallholders with quality seedlings by 2025 comes as Indonesia and Malaysia, the world’s No. 2 producer, face a backlash in Western countries over the environmental toll of the edible oil.

Indonesia is counting on the scheme to help deflect criticism over massive clearance of forests, often home to endangered tigers, orang-utans and elephants, by increasing production on existing plots rather than looking for new plantations.

President Joko Widodo launched the scheme in late 2017, but funding had been disbursed to replant less than 15,000 hectares by last November, against an initial 2018 goal of 185,000 hectares, according to data from the Coordinating Ministry for Economic Affairs.

“Since there has been a growing global backlash against palm oil, it is crucial the replanting program is carried out as soon as possible,” said Thontowi Suhada, a researcher at the U.S.-based World Resources Institute (WRI).

In a country where land ownership is often poorly documented, farmers had been shunning the program because many lack the proof of plot ownership required to register for the scheme, said Bambang Gianto, a farmer based in South Sumatra.

In addition, many lacked the literacy to apply for subsidies or register online, he said.

“There are those who don’t know how to use a computer yet. Some don’t even know what an e-mail is,” said Gianto, who has been trying to help farmers register collectively.

Widodo has now ordered officials to streamline the program, which also aims to help plantations meet requirements to receive Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO) certification.

ISPO, which is mandatory for companies, but voluntary for smallholders, requires that land is legally owned, does not encroach on forests and uses good agriculture practices without burning. Some environmental groups, however, view ISPO as weaker than international certification schemes.

MISTRUST

Indonesia accounts for around 60 percent of the global supply of palm oil, which is used in everything from margarine to cookies and from soap to soups.

Despite its widespread use, it has come under increasing fire over its impact on forest destruction with the European Union planning to phase out biofuels made from oils like palm by 2030.

Musdhalifah Machmud, deputy minister at Indonesia’s Coordinating Ministry for Economic Affair, admitted to flaws in the scheme.

“Communicating the program to farmers turned out to be not as easy as we anticipated,” she told Reuters, adding many farmers also were worried about strings attached to financing.

The government provides 25 million rupiah ($1,722) in subsidies per hectare and initially required farmers to secure bank loans for additional funds.

Mansuetus Darto, chairman of the Palm Smallholders Union, said many members were also wary about the involvement of big plantation companies in case they “take away our land”.

Machmud said the government had now removed bank loan requirements and pledged 26 companies enlisted in the scheme would only help farmers sign up and improve farm management.

The government also intended to employ surveyors to resolve land ownership or rights issues, Machmud said, pledging that all of these efforts should get the program back on track.

SEED QUALITY

Palm trees were introduced in Indonesia in the 1800s by the Dutch, who brought the trees from Africa. In the 1970s, industrial-scale plantations took off and buoyed by their success, many smallholders started growing palm, but often using poor quality seedlings.

Some simply took fallen fruit from neighboring land to plant, said Dono Boestami of the Estate Crop Fund, a state agency in charge of financing the replanting.

Using better seeds could double or even triple yields, as well as producing fruits within only two years, he said.

Smallholders currently produce two to three tonnes of crude palm oil per hectare a year, against 12 tonnes by Malaysian smallholders, according to Indonesia’s agriculture ministry.

Industry analyst Thomas Mielke said a combination of ageing trees and poor seeds meant rejuvenation was crucial.

“If this is not being accomplished, smallholders probably will be facing further decline in yields, and further increases in production costs,” Mielke told an industry conference.

Combined with restrictions on new planting areas, after Widodo imposed a moratorium on plantation permits for three years, growth for palm oil production would slow starting from 2020-2021 and beyond because of ageing trees, he said.

This comes as palm oil futures on the Malaysian exchange trade around the weakest since 2015 at around 2,000 ringgit ($477.90) per tonne after bumper harvests in Indonesia and Malaysia, as well as trade restrictions by some buyers.

The Indonesian Palm Oil Association sees 2018 production at a record 42 million tonnes, but drier conditions due to an El Nino weather pattern may slow output growth this year.

Editing by Ed Davies and Raju Gopalakrishnan

Leave a Reply